Looting of Iraq

by Frank Rich

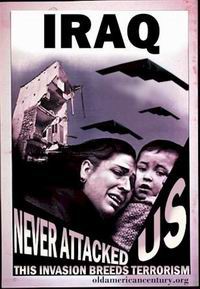

IT’S not just about torture. Even if there had never been an Abu Ghraib, a Guantánamo or an American president determined to rewrite the Geneva Conventions, America would still be losing the war for hearts and minds in the Arab world. Our first major defeat in that war happened at the dawn of the Iraq occupation, before “detainee abuse” entered our language: the “Stuff happens!” moment at the National Museum in Baghdad.

Three and a half years later, have we learned anything? You have to wonder. As the looting of the museum was the first clear warning of disasters soon to come, so the stuff that’s happening at the museum today is a grim indicator of where we’re headed in Iraq: America is empowering the very Islamic radicals this war was supposed to smite. But even now we seem to be averting our eyes from reality on the ground in Baghdad.

Our blindness back in April 2003 seems ludicrous in retrospect. As the looting flared, an oblivious President Bush told the Iraqi people in a televised address that they were “the heirs of a great civilization that contributes to all humanity.” Our actions — or, more accurately, our inaction as the artifacts of that great civilization were carted away — spoke louder than those pretty words. As Fred Ikle, the Reagan administration Pentagon policy chief, puts it in Thomas Ricks’s “Fiasco,” “America lost most of its prestige and respect in that episode.”

That disaster might have been mitigated if our leaders had not dismissed the whole episode as a triviality. But Donald Rumsfeld likened the chaos to the aftermath of a soccer game and joked that television was exaggerating the story by recycling video of a single looter with a vase. Gen. Richard Myers defended our failure to intervene as “a matter of priorities” (we had protected the oil ministry). Lt. Gen. William Wallace, countering a wildly inflated early claim by a former museum employee that 170,000 artifacts had been destroyed, put the number of objects still unaccounted for at “as few as 17.” (The actual number was closer to 14,000.)

The war’s many cheerleaders in the press fell into line. In keeping with the mood of the time, administration enforcers like Charles Krauthammer and Andrew Sullivan damned Mr. Rumsfeld’s critics as fatuous aesthetes exploiting a passing incident to denigrate the liberation of Iraq. In a column in Salon titled “Idiocy of the Week” (that idiot would be me), Mr. Sullivan asked rhetorically who was right about “the alleged ransacking” of the museum, Mr. Rumsfeld or his critics? “Rummy, of course. He almost always is.”

Of course, dear old Rummy’s what-me-worry take on the museum was the tip-off to how he would be wrong about everything that would follow: he reacted with exactly the same disdain and indifference to the insurgency happening under his own nose and to Abu Ghraib. There would be a hasty corrective to the looting, at least: a heroic Marine Reserve colonel, Matthew Bogdanos, commanded a team that ultimately tracked down a bit more than a third of the vanished objects. (It was too late to rescue tens of thousands of additional treasures in Iraq’s National Library and National Archives, both also looted and torched.) But Mr. Rumsfeld’s “Stuff happens!” proved indelible because it so resonantly set forth an enduring theme of the occupation: that the Americans in charge of Iraq were contemptuous of the local populace to whom they were so grandly bequeathing democracy and other fruits of civilization.

The cavalier American reaction to the museum looting was mimicked in the $22 billion reconstruction effort, an orgy of corruption and waste that still hasn’t brought Iraqis reliable electricity. In a new account of the civilian nation-builders in the Green Zone, “Imperial Life in the Emerald City,” Rajiv Chandrasekaran of The Washington Post details how L. Paul Bremer III and his underlings enlisted cronies and apparatchiks rather than those who might actually know anything about the country’s people or their needs. Thus we saddled Iraq with Bernie Kerik, G.O.P. fund-raisers and politically connected young ideologues chosen over more qualified job applicants who knew Arabic. They saw Iraq as a guinea pig for irrelevant (and doomed) experiments, including an antismoking campaign and an elaborate American-style stock exchange. Mr. Chandrasekaran’s book, while nonfiction, is as chilling an indictment of America’s tragic cultural myopia as Graham Greene’s prescient 1955 novel of the American debacle in Indochina, “The Quiet American.”

Read the whole thing

Frank Rich Bush Politics News Iraq Rumsfeld Empire Iran War Imperialism